★★★★☆ The last sensitive white boy, as he bragged in almost those words; a man as important as he was self-important and as full of wisdom as he was full of shit.

I’ve had this book on my shelf for a decade now – my grandparents took my brother and me to a Barnes and Noble when I was a teenager, and I made an edgy teenager decision. At that point, I had looked into Kaufmann’s Zarathustra and heard its thunder – “man is something that must be overcome”, “”one must have chaos in oneself to give birth to a dancing star”. I knew what I was looking for, but it would take me until 2020 to find it when I first came out to myself as a trans woman. More on that later.

Back then, in 2013, I finished Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-85) and attempted Beyond Good and Evil (1886), only to quickly run face-first into a wall of criticism of philosophers I had not read. Kant, Schopenhauer, Spinoza, Epicurus – today, I still haven’t read any of them, but I’ve read the entirety of Existential Comics and can bluff my way through. So when I realized the extent to which Deleuze and Guatteri’s Anti-Oedipus (1972) is based upon On The Genealogy of Morals (1887), I decided to take a detour from that book (more on that later) to go back and actually read this one.

Or rather, the first 3/4 of it – The Case of Wagner and Ecce Homo (both 1888) will have to wait for another time, hopefully not another 12 years. Over the past month or so, I’ve read The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Beyond Good and Evil (1886), “Seventy-Five Aphorisms from Five Volumes” curated by Walter Kaufmann, and finally On the Genealogy of Morals. The order and contents of this list are deliberate – Genealogy‘s subtitle states it is “A Sequel…Meant to Supplement and Clarify” Beyond Good and Evil, and Nietzsche makes frequent reference to that book and others he had written, the relevant passages of which are collected in Kaufmann’s “Seventy-Five”. Finally, although Birth of Tragedy is his first book, the first words in this collection are actually from Nietzsche’s preface to the 1886 edition of the 1872 original. Genealogy makes further reference to this preface, giving the entire reading experience a sense of almost cyclical recurrence, like some manner of endless loop.* In other words, I spent the past few weeks reading the prerequisite material, and this past week, I read Genealogy.

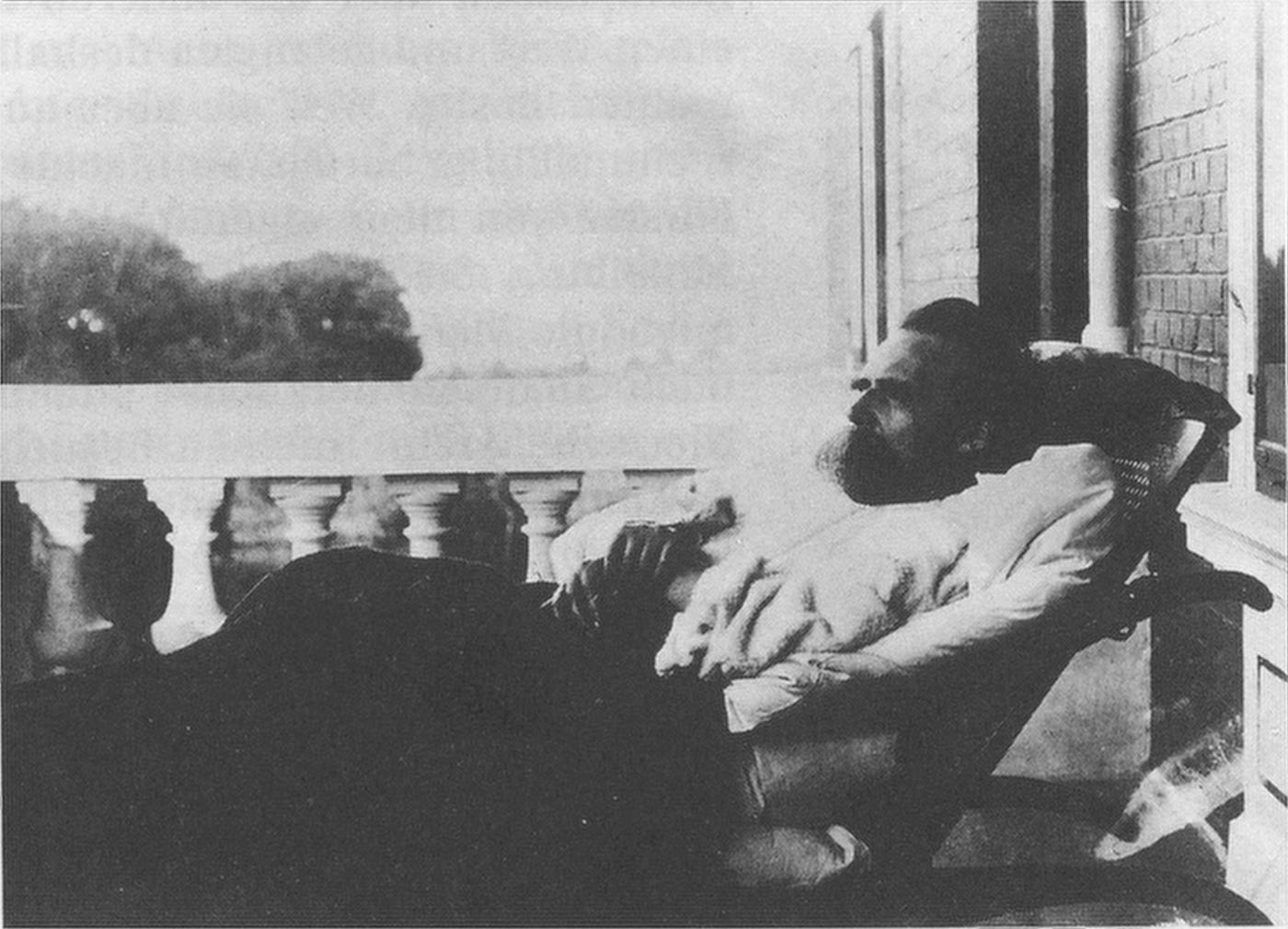

The man I found behind the various masks, both his own and those of others, was more or less what I had expected. The last sensitive white boy, as he boasted in almost those words. Delighting in the wicked joy of value creation even as he feared the values his fellow Germans would create. A man who despised the state and lavished praise upon the Jewish people, but who may well have argued that the noble achievements of Thomas Jefferson justified the horrors he visited upon the enslaved of Monticello. A man whose genius will keep him relevant for at least another hundred years – how will his comments on women and “Asiatic” peoples be received then? In short, a man as important as he is self-important and as full of wisdom as he is full of shit.

For regardless of one’s personal feelings about Nietzsche, one cannot deny his importance to the continental philosophy of 20th century Europe. His identification of the importance of the subconscious was as foundational for Oedipal psychoanalysis as his notion of the will as multiplicity of drives was for anti-Oedipal schizoanalysis. As Kaufmann always delights in pointing out, the works listed above also anticipate Wittgenstein, existentialism, deconstruction, pragmatism, and almost certainly philosophical schools still to come. And even one when knows Nietzsche, does one know one knows him? He has almost certainly been misunderstood far more often than he has been understood properly – just what makes you think you’re special enough to be part of that select few?

If nothing else, Nietzsche, like his best frenemy Socrates, is a gadfly, an irritant, something that must be overcome. He is no Overman, nor did he think he could be. For all his sincere and profound contempt for the Europe of Bismarck and Belle Époque, he was, as he understood, a man of his time despite his most strenuous efforts. He cannot see past his twin blinders of misogyny and white supremacy, and although he is right to laugh at Victor Hugo**, his dismissal of the wretched masses rings considerably more hollow. For all his praise of the Dionysian chorus, one doubts that Nietzsche ever really heard the people sing.

Yet it would be wrong to dismiss him simply as an another bigoted European man at a time when Europe devoured the world. When Nietzsche exhorts the need for the strongest in spirit to be unafraid to stand hated and alone, Kaufmann is always quick to remind us that he rejected Wagner’s inner circle and Wilhelm’s Reich, that in a time of almost universal European anti-Semitism he consistently denounced Germany and exalted the Jews. And furthermore, it would be bad taste to reject the philosopher’s arguments simply out of disdain for the philosopher. Reading Nietzsche, one has to admit, reluctantly perhaps, that he does keep making good points. Sometimes really good points. And sometimes, at high peaks with good air in which Zarathustra calls for his hawk, you understand him perfectly, and all of the tragic masks and tired prejudices and terminal theater kid brain are worth it, and you realize that if necessary you would do it all again and again and again.

Which is good, because if you’re reading 20th-21st century European continental philosophy, you are absolutely gonna have to.

* Not unlike the experience of blasting Gaslight Anthem’s American Slang on no-skip repeat while driving around exurban Detroit, another essential aspect of my 2013.

** What’s the 21st century equivalent of serving as pallbearer for Adolph Thiers as a republican?

Leave a Reply